VIDEO

PODCAST

THE SACRED GEOMETRY OF THE SOUL

To speak of the circle is to speak of eternity. In the ancient world, the circle was not merely a shape—it was a revelation. The Hebrew word Chûg (חוּג) means to circle, to encompass, to embrace. It appears in Job 26:10, where God “has inscribed a circle upon the face of the waters,” and in Isaiah 40:22, “He sits enthroned above the circle of the earth.”

This word does not describe geometry alone, but the invisible symmetry of divine order. The chûg is the movement of completion, the perfect motion that returns to its beginning without loss or break—creation returning to its Creator.

The human soul was made in that same pattern: a living circle drawn by divine intention. Yet through distraction, rebellion, and forgetfulness, humanity wandered outward—becoming linear, fragmented, dismembered. The path of redemption, then, is the return to the chûg, the recovery of the sacred geometry of the heart.

Augustine captured this longing with haunting clarity:

“You were within, and I was without; and there I sought you.”

His lament is the cry of every prodigal consciousness. The journey outward was necessary to awaken the desire to return—but the wisdom of heaven has always been circular. The outer road bends back inward.

God is thus discovered not in the clatter of externals, to which the world calls us with false promises of peace and satisfaction, but in the quiet sanctuary within. He is the still, unchanging centre—the divine axis around which our restless souls revolve, seeking meaning in the shifting shadows and false promises. While we chase echoes and reflections, He remains the origin—the silent heart of all motion, the eternal presence that calls us home from our wandering.

THE HIDDEN LINK BETWEEN CHÛG, ḤĀG, AND HĀGIOS

From chûg arises a fascinating cluster of sacred terms. The root is related to ḥāg (חָג)—to celebrate, to make pilgrimage, to move in a sacred circle. The feasts of Israel, called ḥaggim, were not static commemorations but circular movements around the presence of God. The pilgrim would “go up” to Jerusalem, yet in truth, he was moving inward to the heart of divine communion.

This same root echoes in the Greek hagios (ἅγιος)—holy, set apart, consecrated. The spiritual resonance between ḥāg (Heb.) and hagios (Grk.) is unmistakable. Both speak of the sacred act of circling around what is divine: holiness as orbit, not isolation. To be holy is to live within the circumference of God’s presence.

It invokes the concept of living with the “circle” of God, that is His sacred embrace, where provision and protection are assured.

“You shall settle in the land of Goshen and be near me—you and your children and grandchildren, your flocks and herds, and everything you own. And there I will provide for you…” —Genesis 45:10-11

Goshen is etymologically linked to nāgash (נָגַשׁ), “to draw near, to approach, intimate union.” Goshen thus means the place of approach, where one comes close, near enough to be united with the source of life. In fact Goshen (G-SH-N) is a perfect anagram of Nagash (N-G-SH).

In spiritual practice, this inward circling manifests as meditation, prayer, contemplation, abiding, tarrying, the fostering of the inner life. The Hebrew hagah (הָגָה)—to meditate, utter, murmur—shares the same sonic harmony. We find hagah again in the word “haggle.” Joshua 1:8 commands:

“This book of the law shall not depart from your mouth, but you shall meditate (hagah) on it day and night.”

To hagah is to keep circling a truth in your mouth until it imprints the heart. It is the mental and spiritual choreography that restores the mind and life to divine rhythm.

Thus, chûg, ḥāg, hagah, and hagios form a spiritual constellation. They are words of movement, remembrance, and return. They describe not merely religion but rhythm—the circle of communion that pulls humanity back into divine alignment.

THE PHILOSOPHY OF RETURN

Pascal, in his Pensées, observed that the human heart contains an “infinite abyss that can only be filled by an infinite and immutable object.” Like Augustine, Pascal recognised that man’s restlessness is evidence of his exile from the centre. Rational knowledge alone cannot still the heart, for reason is linear—it analyses, dissects, explains; it is processional. But the soul’s longing is circular—it desires wholeness, embrace, homecoming.

In the same way, Greek philosophy spoke of phronēma—the mind’s orientation or disposition. Paul uses this word in Romans 8:6:

“The mind [phronēma] set on the Spirit is life and peace.”

This is not mind in the contemporary sense. Translating phronema as mind is an unfortunate miss-translation since the Greek word for mind is actually “nous” (cf. Romans 12:2). Phronema is not merely the faculty for thinking, but a posture of being, a direction of the inner compass and internal framework. The consciousness turned outward toward the flesh leads to fragmentation; the consciousness turned inward toward the spirit/Spirit restores the circle.

Augustine’s inward turn, Pascal’s existential ache, and Paul’s spiritual phronēma all converge upon the same mystery: that truth is not discovered outwardly but remembered inwardly—the consciousness elevated from sensuality to spirituality. Repentance (metanoia) is not moral regret but mental reorientation—a turning of the entire being from the periphery to the center. Metanoia is changing where you look for salvation.

The mystics called it the return to the heart.

THE PRODIGAL CIRCLE

Genesis 45 contains one of Scripture’s most tender revelations of this mystery. When Joseph meets his brothers after long years of separation, he tells them: “You will stay close by me, and I will give you the best of the land.”

The words echo the Father’s heart for all returning children. Proximity is privilege. To stay near the beloved is to inherit abundance.

The prodigal son of Luke 15 mirrors this same circle of return. He goes outward, exhausts himself in the far country, and finally awakens—not by discovering something new but by remembering where he came from. His journey is the arc of every soul: departure, hunger, remembrance, and return. The Father’s embrace completes the chûg—the divine circle closed again. Thus,

“What you seek is seeking you.” —Jalāl ad‑Dīn Rūmī (Sufi Poet)

Scholars note there is no definitive source in Rumi’s Persian corpus with that exact phrase, however, One Persian couplet often cited:

هر چیز که در جستن آنی آنی

“Har chiz keh dar jostane āni, āni”

which can mean,

“Whatever it is that you are seeking, you are it.”

Repentance, then, is not shame but geometry. It is not downward humiliation but the curved motion of love drawing us upward, homeward. The esoteric and exoteric—mystery and manifestation—are reconciled in this movement. What was once hidden within now reveals itself without, and the circle is restored.

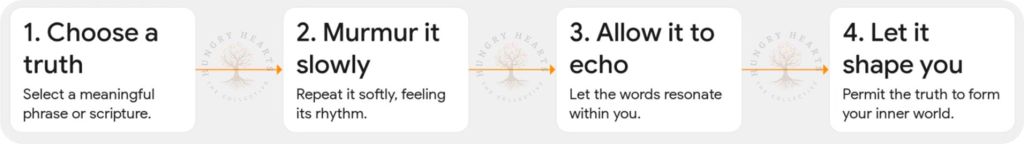

THE INNER MEDITATION: HAGAH AS SPIRITUAL PRACTICE

The practical dimension of this mystery is found in hagah—the slow, deliberate murmuring of divine truth. The seeker does not rush; he circles the Word as a lover traces familiar lines upon a beloved’s face. Hagah is the art of staying—of allowing truth to echo until it becomes flesh in thought and feeling.

While the world clamours for acceleration—urging us to catch up, to do more, to be more—the Spirit whispers a contrary invitation: slow down. The noise of the age equates haste with progress, but heaven measures movement not by speed, but by stillness.

Notice how frantic striving leaves us splintered, drained, and hollow—like shards scattered from the wholeness we once were. In our rush, we lose not merely time but presence; not merely focus, but self. Yet in slowing down, we find ourselves gathered again. We become centred, rooted, and quietly strong—established upon that unshakable foundation that is God Himself.

The machinery of the world system is intentionally designed to keep humanity distracted, perpetually chasing the next demand, purchase, or performance. It’s paradigm is an inversion of right-eousness (correct alignment). Its rhythm is engineered to drown out the still, small voice within. For when a soul is hurried, it is easily subjugated; when restless, it becomes pliable to manipulation. A scattered mind cannot discern truth; a weary heart cannot resist deception. This is why so many feel orphaned and abandoned.

It is in this context that the old saying proves profoundly true:

“The devil’s business is busyness.”

For nothing delights the adversary more than a believer too occupied to pray, too distracted to become conscious, too rushed to listen. In keeping us endlessly occupied, he need not destroy us—only exhaust us. But when we choose to slow down, to stop participating in the universal panic, to abide, to breathe again in the presence of the Eternal, we subvert the entire machinery of manipulation. We return to the still point within—where God is found not in the whirlwind, nor the fire, nor the noise, but in the eternal presence that waits for us when all else is silent and welcome us home with open arms.

When the Hebrew text says, “Blessed is the man whose delight is in the law of the LORD, and on his law he meditates [hagah] day and night” (Psalm 1:2), it reveals a rhythm of abiding rather than achieving. The purpose is not information but formation. Meditation is participation in divine speech; it is the sound of God resonating within the human chamber. Rest is agreement with the Lord’s words, “it is finished” (John 19:30), and rejecting the adversaries words, “save yourself.”

To hagah is to eat spiritual food. As the body is nourished by bread, the soul is nourished by revelation. Without this inner feeding, we revert to animalistic existence—driven by instinct, unaware of the Spirit’s dimension. But faith, born from hearing, gives structure and sight to the inner faculties. It fuels the inner life. Only when these are awakened can we perceive our identity as new creations (2 Corinthians 5:17–18).

THE CIRCLE AND THE CROSS

At the centre of the chûg stands the Cross—the axis where time and eternity meet. The Cross is not only the means of salvation but the symbol of divine symmetry: vertical union with God intersecting horisontal reconciliation with humanity. Our vertical relationship supports our horisontal relationships. The one who abides in this intersection lives within the hagios, the circle of holiness.

In ancient iconography, the halo around the saints was not mere decoration—it represented the radiant circumference of divine presence surrounding the soul. The circle of light signified not separation from the world, but reintegration into the divine order.

So too in the believer’s life: holiness is not distance (external) but closeness (internal). The more one abides in Christ, the more one moves within His gravitational field. Striving ceases; the fruit of the spirit (small “s”) grows naturally. The law of life in Christ Jesus completes the law of return.

THE INNER CIRCLE OF RETURN

To live in the chûg is to live consciously near the Presence. To hagah is to sustain the rhythm of remembrance. To ḥāg is to celebrate the return by embodying it in private and communal practice. Together, these words outline the mystical pattern of restoration—the circle of inward homecoming, where all beginnings and endings meet in God.

The outward world will always pull us toward dispersion, dissolution and dissipation. But the inward world—the kingdom within—calls us to gather, to unify, to return to the one center. This is the true pilgrimage: the soul’s rotation back to its axis in Christ. Now consider the words of Christ Himself within the aforementioned context:

“Being asked by the Pharisees when [and where] the kingdom of God would come, he answered them, “The kingdom of God is not coming in ways that can be observed, nor will they say, ‘Look, here it is!’ or ‘There!’ for behold, the kingdom of God is in the midst of you.” —Luke 17:20-21

KEY STATEMENT

Spiritual maturity is not linear progress but circular return—the soul’s journey back to its divine center, where the Word is remembered, the Spirit is known, and the Father’s embrace becomes the horison of all being.

DEVOTIONAL PRAYER

Lord, You are my center and my circumference.

You encircle me with mercy and draw me inward with love.

Teach me to hagah upon Your Word until my heart beats in rhythm with Yours.

Restore the sacred geometry within me—

The harmony of thought, feeling, and faith.

May I dwell close to You, in the best of Your land,

And find my rest in Your unbroken circle of peace.

Amen.

QUESTIONS FOR REFLECTION

- What “outer circles” have distracted your soul from its center in God?

- How might practicing hagah—slow, meditative repetition (haggleing of Scripture—reshape your inner world?

- In what ways does holiness (hagios) function as divine orbit rather than moral distance?

- How does understanding repentance as return rather than regret transform your spiritual journey?

- Where do you sense the Spirit inviting you to “stay close” and abide in the best of the land?

KEYWORD GLOSSARY

| Word | Language | Transliteration | Meaning & Etymology | Theological Insight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| חוּג | Hebrew | Chûg (khoog) | Literally “circle,” “sphere,” “to encompass,” or “to inscribe.” Found in Job 26:10; Isaiah 40:22. Root conveys the act of drawing a circular boundary—representing completeness, divine order, and cosmic containment. | Symbolises the divine enclosure of life—God’s sovereignty surrounding creation. Spiritually, chûg reveals the rhythm of return, the geometry of grace. |

| חָג | Hebrew | Chāg (khag) | “Feast,” “festival,” “pilgrimage.” From the root chûg (“to circle”), indicating sacred procession or cyclical worship. Used for the great feasts (Exodus 23:14). | Every feast was a circle of return—a movement back into remembrance of divine covenant. Worship as circular communion rather than linear duty. |

| הָגָה | Hebrew | Hāgāh (hah-gah) | “To meditate,” “murmur,” “utter softly.” Appears in Joshua 1:8 and Psalm 1:2. Connected conceptually to chûg—inner circling of the mind around divine truth. | Represents the meditative orbit of faith—the repetition and internalisation of the Word until thought and spirit align with God. |

| ἅγιος | Greek | Hagios (hah-gee-os) | “Holy,” “set apart,” “sacred.” Possibly related by sound and concept to Hebrew chāg (feast). Denotes that which belongs entirely to God. | Holiness as orbit: living within the gravitational pull of divine presence, revolving continually around God’s nature. |

| φρόνημα | Greek | Phronēma (fro-nay-mah) | “Mindset,” “orientation,” “inner disposition.” From phroneō, “to think” or “to be minded.” Used in Romans 8:6. | Describes the inner compass of the soul—its spiritual inclination. The phronēma of the Spirit restores the circle of life and peace. |

| μετάνοια | Greek | Metanoia (meh-tah-no-yah) | “Change of mind,” “repentance.” From meta (“after, beyond”) + nous (“mind, perception”). | True repentance is return to the centre—the mind’s reorientation toward divine reality rather than mere moral remorse or salvation in externalities. |

Leave a comment