TL;DR

Let us return—to the place where it all began, where men and women stood side by side in one accord, waiting in the Upper Room for the outpouring of divine fire. The Spirit did not descend upon the masculine alone nor the feminine alone, but upon both, united in purpose, restored to power. For as it is written,

“One will chase a thousand, but two will put ten thousand to flight.” –Deuteronomy 32:30

Exponential Power comes from unity not division.

When we allow the world’s cultural engineers to divide us—when we wage war between man and woman instead of standing together against the true enemy—we surrender to a satanic plan designed to weaken us. But when we embrace our God-given design, honouring strength where it is strong and grace where it is gentle, the unity of heaven flows through us again.

We were never meant to be alone. God Himself declared, “

It is not good for man [a human, earthing] to be alone” —Genesis 2:18

This truth transcends marriage—it speaks of divine partnership, of masculine and feminine forces designed to reflect the image of God together.

The war between men and women is not natural—it is engineered; for when unity stands, Babylon falls. As we draw near to Christ the chasm of separation between us is eviscerated.

KEY STATEMENT

VIDEO (SOCIETAL FEMINISATION)

VIDEO (BLOGPOST)

PODCAST

“No,” says Jephthah, standing with the blunt clarity of one who has seen God’s hand, “will you not take what your god Chemosh gives you? Likewise, whatever the LORD our God has given us, we will possess” (Judges 11:24). The sentence is short, juridical and fierce—not an exercise in culture-war rhetoric but a theological claim about origin and authority: possession is dependent upon who gives. In the context of Israel’s contested territory the remark reads like a legal brief; in the life of the soul it reads like a summons: recognise the source of your life, accept what the Lord has given, and step into the calling He grants.

When I read Jephthah now I do not only see a man litigating land. I hear a deeper lament and invitation: we have accepted idols of our own making—cultural gods that give us ways of seeing ourselves—and we have allowed those gifts to shape our institutions, our families and our inner lives. The remedy Jephthah points to is not aggression for its own sake, but the reclamation of rightful possession under God. For both men and women, for the life of the Church, this reclamation begins with initiation: the rites, the labours, the spiritual practices that move us from fragile infancy into stable adulthood in Christ.

By embracing the world’s definition of masculinity and femininity, we have fallen prey to one of Satan’s oldest deceptions. The issue is not a contest of who is right or wrong—it is a call to restore divine balance within the Church, where strength and grace walk hand in hand under the authority of Christ.

In this post I want to do five things:

- First, to name the cultural diagnosis: the feminisation (and infantilisation) we see across institutions, including the Church, and the consequences of father-absence and lack of ritual initiation.

- Second, to sketch key theoretical frameworks—Helen Andrews’ “Great Feminization” thesis, J. D. Unwin’s classic sociological argument in Sex and Culture, anthropological work on rites of passage (Van Gennep, Turner), and contemporary social science on father-absence and outcomes.

- Third, to trace how the Church’s own practices have too often enabled spiritual infantilisation—pseudo-rituals and managerial structures that shortcut genuine initiation.

- Fourth, to set out a theological corrective rooted in Scripture: covenant, spiritual communion with Christ, and a recovery of the roles and rites that form stable masculinity and femininity.

- Fifth, to propose practical pathways the local Church might adopt so that men and women can be initiated, mature and bear witness to a gospel that heals both sexes and the civic order.

I will not shy away from uncomfortable observations: demographic shifts in institutions produce cultural effects; the collapse of initiation produces immaturity; and the removal of fathers from domestic life correlates with social dislocation. But I will not use these observations to scapegoat or demonise. The Church is called to heal by truth and grace. If the world has more influence on the Church than the Church upon the world, we must humbly recover our vocation to form human beings who are whole in Christ.

“So Jesus said to the Jews who had believed him, ‘If you abide in my word, you are truly my disciples, and you will know the truth, and the truth will set you free.’”

I. A SHORT DIAGNOSIS: FEMINISATION, INFANTILISATION AND THE LOSS OF RITE

We live under a strange double movement. On the one hand, the institutions of the West—law, medicine, the academy, much of the media—have seen an unmistakable increase in female presence and leadership over the last two decades. Scholars and journalists have observed that, once a profession passes parity, it frequently continues toward a majority female workforce; this demographic shift brings different styles of communication, risk assessment and institutional norms into the institutional bloodstream.

Western institutions are currently undergoing a parallel, though culturally driven, deregulation. This process, termed “The Great Feminisation,” represents an unprecedented demographic and cultural shift within vital societal institutions. The core issue is not one of social justice or gender equity, but one of institutional resilience and functional integrity. The rapid transition of key professions from majority-male to majority-female composition has introduced a new paradigm of group dynamics, creating systemic risks that threaten their core missions.

The recent and accelerated nature of this demographic shift is a critical factor, as many of these tipping points have occurred only within the last decade. This is not a gradual evolution, but a contemporary phenomenon with immediate consequences:

- Law Schools: Became majority female in 2016.

- Law Firm Associates: Became majority female in 2023.

- The New York Times Staff: Became majority female in 2018.

- Medical Schools: Became majority female in 2019.

- College-Educated Workforce: Became majority female in 2019.

The 2005 resignation of Harvard President Larry Summers serves as a seminal case study in this new cultural dynamic. After suggesting that innate aptitude differences might partly explain female underrepresentation in the hard sciences, Summers was subjected to a campaign that exemplified an emergent feminine model of conflict resolution. Instead of logical refutation—indeed, experts affirmed his statements were within the scientific mainstream—his opponents relied on emotional appeals and public shaming. The reaction of MIT biologist Nancy Hopkins is instructive:

“When he started talking about innate differences in aptitude between men and women, I just couldn’t breathe because this kind of bias makes me physically ill.”

This incident marked a cultural turning point. Helen Andrews frames this as “the Great Feminization,” arguing it helps explain the cultural phenomenon usually labeled ‘wokeness’—not as a single ideological engine but as an emergent culture shaped by female majorities in key institutions. The Compact Magazine piece lays out data points and a persuasive cultural narrative about how institutional norms alter as demographics change.

“The problem is not that women are less talented than men or even that female modes of interaction are inferior in any objective sense. The problem is that female modes of interaction are not well suited to accomplishing the goals of many major institutions. You can have an academia that is majority female, but it will be (as majority-female departments in today’s universities already are) oriented toward other goals than open debate and the unfettered pursuit of truth. And if your academia doesn’t pursue truth, what good is it? If your journalists aren’t prickly individualists who don’t mind alienating people, what good are they? If a business loses its swashbuckling spirit and becomes a feminized, inward-focused bureaucracy, will it not stagnate?” —Helen Andrews

This demographic transformation is, of itself, neither good nor evil. But it interacts with other social changes—the breakdown of fatherhood, the collapse of initiation rites, and the Church’s drift into managerial patterns to produce a markedly different civic temperament. When institutions are populated by people who prize safety, emotional validation and cohesion over adversarial testing and risk-taking, the rules of disagreement and the forms of authority shift. Some critics argue this undermines confrontation, thick argument and intellectual ruggedness; others applaud the more humane cultures that emerge. The point for us is diagnostic: the shape of institutions affects the spiritual ecology of a people.

More importantly, we must ask whether the outcome this change is producing is conducive to male and female fulfillment.

Concurrently, western Christianity has quietly infantilised many of its devotees. There is an epidemic of “protracted infancy,” as various theologians and pastors have noted: believers who remain spiritually adolescent despite years of church attendance. Many never had access to serious initiation. They were baptised, taught sermons and given programmes, but were not led through the type of formative spiritual disciplines—sacramental, ascetical, communal—that slay the small self and allow a new adult identity to emerge. This problem is sociological and pastoral: we have created Christian subcultures that sometimes reward sentiment and involvement while failing to cultivate interior formation.

Anthropology points us to what is missing. Van Gennep and Victor Turner, whose work on rites of passage has become canonical, show that cultures which sustain themselves long-term have formal mechanisms for moving adolescents into adult roles. Where those rites are abandoned or become purely symbolic, the community loses its ability to transmit the moral and vocational goods of adulthood. The absence of such rites in modern western churches is not accidental; it is the result of modernity’s egalitarian impulses, the bureaucratisation of worship, and a consumer mindset that prizes immediate comfort.

The social science on father-absence deepens the diagnosis. Research demonstrates substantial correlations between father absence and poorer outcomes for boys and girls: lower educational attainment, higher risk of incarceration and fewer stable unions. The Institute for Family Studies and academic reviews synthesise a large body of evidence linking the breakdown of the two-parent family with measurable social effects. Where fathers are absent, initiation into adult male roles is less likely to occur naturally within the domestic sphere, and boys are more likely to become adrift.

If institutions feminise without a corresponding cultural architecture for male initiation, the result is often a cultural mismatch. Men are left without clear roles; women are pressured into occupying functions they were never fully formed to perform culturally; and both sexes end up impoverished of the complementary virtues that make social life—and civilisation—possible. That is the diagnosis. It is neither simplistic nor reducible to blame. It is an attempt to name structural factors that bear on spiritual formation.

II. THEORIES IN DIALOGUE: ANDREWS, UNWIN, PAGLIA—USEFUL, TROUBLING, AND NOT ORTHODOX

We must treat contemporary theories with care. Some of the most provocative accounts are those that locate cultural change in demographic processes or sexual mores rather than purely in political ideology implemented through cultural engineering. Helen Andrews’ thesis is one such example: she contends that the phenomenon we call ‘wokeness’ is tightly correlated with demographic feminisation of elite institutions; as these institutions reached parity and then majorities of women, their operating norms changed. The piece is polemical—it presses data for cultural inference—but it is worth attending to because it reframes familiar puzzles. It does not answer every question, and it neglects the deeper spiritual analysis of sin—seeking self-salvation apart from God; but it helps explain timing and institutional dynamics.

Another uncomfortable, older thesis is J. D. Unwin’s Sex and Culture (1934). Unwin argued that sexual restraint—specifically, cultural strictures around pre-marital sexual conduct and institutionalised monogamy—correlated with civilisational vigour. He claimed that once sexual liberty increased, societies eventually lost the organising energy that had sustained their creative achievements; crucially, his claim is that the process is largely irreversible. Unwin’s thesis is contested, methodologically idiosyncratic and ethically fraught in places; but as a pattern-seeking exercise it tells a similar story: sexual mores, family structure and cultural energy are connected. Caution required; nevertheless the thought experiment helps us see why the collapse of initiation and sexual mores could have long-term civic consequences.

Camille Paglia gives us another angle: she laments the loss of female solidarity that once characterised pre-modern women’s social worlds, arguing that women’s modern incorporation into male spheres brought both gains and losses—including the erosion of certain communal structures that once supported female identity. Paglia’s arguments are often rhetorical and iconoclastic, but her historical instinct deserves attention: social roles and support networks can be sources of psychological carrying power; their disintegration leaves gaps that modern institutions have not yet replaced.

There are critics of the “feminisation as cause” thesis who argue the move is partisan or selective. Richard Hanania, for instance, has argued that “feminisation” arguments can be used as partisan shorthand, and that structural explanations must take political incentives into account. The debate is ongoing and requires nuance: demographic shifts matter, legal incentives matter, educational changes matter, and spiritual formation matters. The Church must hold all these threads without collapsing into conspiratorial thinking.

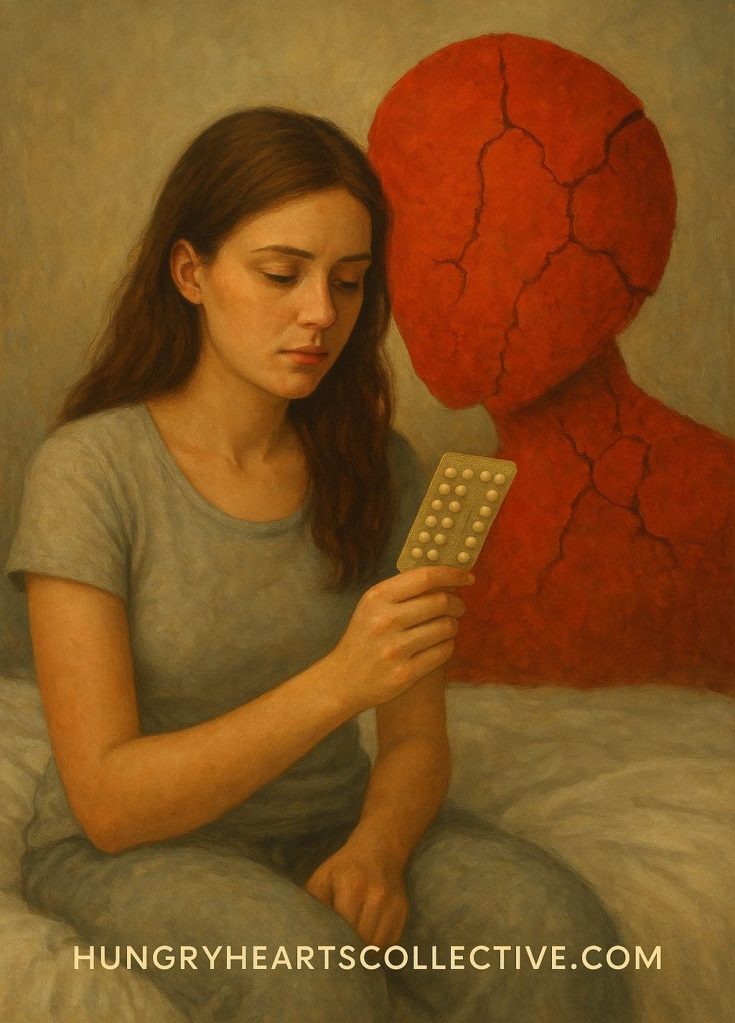

The introduction of the Pill in the 1960’s is another factor that empowered man’s rebellion against God and the delusion of self-salvation. It was hailed as a triumph of modern science—a small tablet that promised liberation, autonomy, and control. Yet beneath its veneer of progress lay a quiet revolution that would alter not only reproductive habits but the very fabric of morality, relationships, and culture.

Before the Pill, sexuality was tethered—both biologically and socially—to responsibility. Intimacy carried with it the potential for new life, and that potential imposed a natural restraint. The act of union, though private, carried public consequence; it demanded foresight, fidelity, and moral weight. But with the separation of sex from procreation, desire was unchained from duty. The sacred became casual, the covenantal became contractual, and pleasure was stripped from its generative meaning.

The Pill offered not merely birth control, but consequence control. It promised that one could indulge the deepest instincts of the flesh without bearing the fruit of responsibility. In doing so, it subtly redefined freedom—not as the power to govern oneself, but as the license to do as one pleases. What began as an instrument of convenience became a catalyst for a wider cultural shift: the desacralisation of the body, the commodification of intimacy, and the fragmentation of the family.

As the generations unfolded, the effects became increasingly visible.

- Marriage rates declined, as commitment was replaced with cohabitation and convenience.

- Birth rates plummeted, creating entire societies where ageing populations now outweigh the young.

- Pornography and promiscuity flourished, feeding a culture of consumption rather than covenant.

- Divorce rates soared, not because evil triumphed overnight, but because the very meaning of love was quietly rewritten—from self-giving to self-seeking.

When the sacred link between sex and life was severed, the moral architecture of civilisation began to crumble. Every culture that survives the test of history holds a shared reverence for family, fidelity, and the sanctity of life. Anti-natalism has long been a defining mark of civilisations in decline—a symptom of cultures that have lost faith in their own future.

The Pill, though chemical in nature, became philosophical in effect. It taught us to see fertility as a flaw rather than a gift, to treat conception as an inconvenience rather than a calling, and to view the womb as a space to be managed rather than a sanctuary to be honoured.

Moreover, it introduced a subtle antagonism between the sexes. The very technology that promised to liberate women from the “burden” of biology simultaneously made them more vulnerable to exploitation. Men were freed from responsibility while women bore the invisible cost—physically, emotionally, and spiritually. Thus began the modern gender war, in which unity gave way to suspicion, and partnership to power struggle.

In truth, the cultural collapse we witness today—the breakdown of marriage, the crisis of fatherhood, the confusion of gender, and the epidemic of loneliness—can all trace some lineage back to that moment when the biological covenant between love and life was broken.

Civilisations are not destroyed by cataclysm alone; they often die by degrees, when the sacred is secularised, when convenience replaces conviction, and when technology is exalted over truth.

The Pill did more than prevent pregnancy—it prevented posterity. It interrupted not only the cycle of birth but the continuity of meaning. For when a people no longer see life as holy, they soon forget how to live wholly.

True liberation, then, is not found in mastering the body, but in honouring it. Not in silencing fertility, but in reverencing the divine rhythm that makes man and woman co-creators with God. Until we restore that sacred vision, our culture will continue to drift—pleasured, medicated, and yet profoundly barren.

III. THREE PATHOLOGIES IN THE CHURCH: INFANTILISATION, PSEUDO-INITIATION, AND LINGUISTIC CAPTURE

If the modern world has shifted in ways that matter morally and socially, the Church has not been immune. I want to name three particular pathologies:

1. Infantilisation. Many Christians have their deepest longings left unaddressed. They know church rituals, they attend programmes, but they have not undergone a death and rebirth in Christ that re-configures identity at the center. The result: congregations full of long-time attendees who remain spiritually adolescent. Theologically this is tragic—the new creation is meant to be an adult identity, not an extended adolescence. Pastoral writers note this pattern repeatedly: prolonged spiritual infancy breeds quarrels, factionalism and ineffective witness.

2. Pseudo-initiation. Our liturgies and programmes sometimes masquerade as initiation while accomplishing little. A children’s holiday club, repeated altar calls that substitute emotional high for conversion, or managerial onboarding for new members do not constitute rites which slay the ego and re-birth the soul in disciplined belonging. Van Gennep’s distinction between separation, liminality and reintegration offers a useful rubric: without genuine liminal formation the ritual is cosmetic.

3. Linguistic capture / Christianese. This is subtle but vicious. We have developed a specialised vocabulary that sometimes obscures rather than clarifies the transformation we need. Words like “spiritual” get diluted into vague therapeutic categories; “maturity” into mere attendance; “prayer” into a wish list. Recovering domain-specific vocabulary—covenant, initiation, kenosis, discipleship as formation—matters. The Church must name the process it wants to initiate: movement from Egypt (childhood) to Canaan (mature stewardship), as we have described in previous posts. That language matters because Christian maturity is not a self-help project; it is a covenantal, sacramental and spiritual re-formation. (Scriptural anchors: Genesis 2:18; Ecclesiastes 4:12; Christ’s death and resurrection as the centre of initiation.)

IV. THEOLOGICAL CORRECTION: COVENANT, COMMUNION, AND INITIATION INTO CHRIST

If the problem is structural and spiritual, the remedy must be theological and practical.

1. Covenant as Ownership. Jephthah’s brief legal move—“whatever the LORD our God has given us, we will possess”—invites us to think covenantally. What God gives, He gives within a covenantal economy. To possess rightly is to recognise the covenant and live by its obligations. Teaching covenant is not optional; it is the grammar of Christian identity. Covenant language reframes ownership not as entitlement but as stewardship: we are stewards of God’s gifts for the flourishing of others and the glory of God.

2. Spiritual Communion (vs purely liturgical forms). Communion is not simply an item on a liturgical checklist. True spiritual communion—direct, interior participation in Christ—is the heart of Christianity. Historic Christianity has both exoteric—words, sacraments, liturgy—and esoteric—inner transformation & spiritual formation—dimensions. The two must be held together.

If the Lord’s Supper is a sacrament then it must impart grace and be evidenced by transformation. Litturgical communion does neither, it merely points to the source of grace that transforms: Christ Himself. Precisely because of this we need to move from childish symbols such as freudian “birds and bees” and get down to the brass tax of spiritual intimacy with Christ. True communion as apposed to liturgical communion is both sign and instrument of union with Christ. Initiation into Christ requires both the external sacrament and steady inward practice (silence, prayer, fasting, confession, spiritual direction) that cultivate inner communion. Without inner communion, Christian ritual becomes cosmetic.

3. Rites of initiation into masculinity and femininity. Anthropologists show that cultures use initiation to pass the moral and vocational torch. The Church can reclaim this truth sacramentally and pastorally: men need forms of initiation into sacrificial, responsible, creative masculinity; women need forms of initiation into embodied, relational, creative femininity. These are not caricatures of gender but the recovery of complementary, Christ-shaped vocations. Fathers and mothers—and the wider ecclesial family—have a role. Where fathers are absent the Church must not simply replace but initiate: mentors, structured programmes of formation, cross-generational apprenticeship that take boys into virile discipleship and girls into mature womanhood. Such initiation will contain tests, commitments and rites that mark a movement from childhood into adult responsibility (a functional parallel to Van Gennep’s separation-liminal-reincorporation schema).

4. The cross as horizontal reconciler. The cross demonstrates that our vertical relationship with Christ—supports horisontal relationships with each other. This is crucial. The cross reconciles male and female, not by erasing distinction, but by reorienting both toward costly love, mutual submission and sacrificial service to Christ first. Only in Christ do masculine strength and feminine receptivity find their true flourishing: the masculine learns to love that lays down power; the feminine receives and gives life in ways that are not merely expressive but formative. The cross unifies by making each party die to lesser idols of power, control and resentment.

V. PRACTICAL PROPOSALS FOR THE LOCAL CHURCH (A FRAMEWORK)

If we are to reclaim healthy masculinity and femininity, and to initiate adults in Christ, here are practical pathways:

1. Re-introduce formal rites of initiation. Not club initiations or hazing, but sacramental and vocational rites: publicly acknowledged commitments, periods of deliberate liminality (retreats, mentorships, apprenticeships), and reintegration ceremonies that mark a changed identity. These rites should be catechetical, ascetical and community-bound.

2. Develop fathering and mentoring networks. Where biological fathers are absent, the Church must create fathering structures: older men apprenticing younger men; intergenerational households or networks; programmes that teach trade, vocation, spiritual leadership and household stewardship. Research on father-absence shows the long-term harms of neglecting this domain; the Church must be a corrective presence.

3. Reclaim teaching on covenant and ownership. Preaching and discipleship must renew covenant language: God gives; we receive; we act; we steward. This counters both entitlement and martyrdom. Use of Scripture (Genesis 2; Ecclesiastes 4; Pauline formation texts) must be integrated with practical catechesis.

4. Train women and men for their complementary ministries. This is not a call to roll back women’s participation in public life; rather it is a plea for the recovery of complementary formation: formation that strengthens men to be stable, sacrificial leaders and women to be equally powerful in relational, creative, moral authority. Such formation will produce leaders who are neither brittle nor domineering, neither fragile nor domineeringly soft.

5. Resist cultural capture without moral cowardice. The Church must be able to disagree well. The institutional feminisation of public life has changed norms; we must not mimic the worst of either sex. We must train people in civil argument, in moral courage and in the patience to bear one another’s weaknesses without abandoning truth.

VI. CAN WE PUT THE TOOTHPASTE BACK INTO THE TUBE? (ON UNWIN, ISLAMIFICATION, AND COMPLEXITIES)

Is this process is reversible?—can we put the toothpaste back into the tube? Unwin argued it is not. He saw sexual liberalisation and the decay of sexual restraint as correlated with the decline of civilisational energy and irreversibility. Others find his analytic sweep too deterministic and worry that his thesis can be misused to police sexuality in oppressive ways. We must say: his work is a sober provocation rather than gospel truth. It invites us to consider whether some social changes carry long temporal costs.

The rise of patriarchal Islam is a social confirmation of Unwins thesis that correlates the rise of a society with the sexual restraint of its females. Some sociologists argue the female desires structure—which explains hypergamy and the female innate biological and thus psychological need for a partner that can provide safety and resources. In practice this translates into the attraction to status, power and wealth in order to raise offspring. There is nothing wrong with this, it simply provides us with more information. A thesis that many analysts note: where modern secular orders weaken, some communities offer alternative orders, and religion in varied forms can be attractive for its structure. Observers have noted greater religiosity among some immigrant groups and the attractiveness of stricter moral codes where modern institutions feel unreliable.

In a strange and ironic twist, toxic feminism is giving birth to the very conditions it claims to resist. By dismantling the natural harmony between the masculine and the feminine, it has bred a culture of isolation and distrust—where women feel increasingly unsafe, not because men are stronger, but because society has severed the sacred bond of mutual protection. In rejecting the complementary strength of the masculine, modern feminism has stripped itself of the very covering that once safeguarded the feminine spirit.

Now, as women cry out against the dangers of a world they helped unmoor, the true solution quietly re-emerges: a return to order, to divine polarity, to the original design where strength and tenderness coexist, not in competition, but in covenant. It is only when the masculine is allowed to stand as protector, and the feminine as nurturer, that peace and safety can be restored to the human soul—and to civilisation itself.

This is an observation about human social psychology, not an endorsement of any political movement; it highlights the Church’s pastoral task: if women and men seek robust moral ordering, the Church must supply a humane and freedom-honouring alternative rooted in Christ. We must not conflate descriptive sociological claims with prescriptive political advocacy. Nuance is essential.

VII. A TABLE OF KEY SOURCES (SHORT, USEFUL)

Below is a compact table summarising the main external references I used and their key findings. (I have cited the most load-bearing claims above in the text; the table helps you locate the essays and studies.)

| Claim / Topic | Source (short) | Key finding |

|---|---|---|

| “The Great Feminization” thesis (institutions shifting values as they feminise) | Helen Andrews, Compact Magazine, “The Great Feminization” (Compact). | Argues institutional norms shift as demographic feminisation occurs; links timing of changes to professional majorities. |

| Sex, culture and civilisational energy. | J. D. Unwin, Sex and Culture (1934). (Berean Patriot). | Argues sexual restraint correlates with civilisational success; controversial and contested but provocative for long-term pattern thinking. |

| Camille Paglia discusses: Free Women, Free Men: Sex, Gender, Feminism. | The Seattle Public Library’s podcasts of author readings and library events (spl.org). | She challenges current gender theory for its avoidance of biology, opposes the bureaucratic dominance of post-structuralist jargon in academia, and calls for a new feminism marked by equality, respect and mutual responsibility, not by blame or hierarchy. |

| Father-absence and social outcomes. | Institute for Family Studies; S. McLanahan et al., review (PNAS/PMC) (Institute for Family Studies). | Father absence correlates with poorer educational, economic and social outcomes for children. |

| Unduly protracted infancy. | C.S. Lewis Institute (Unduly Protracted (Spiritual) Infancy). | Identifying the underlying problem is neither heresy nor apostasy but worldliness and spiritual immaturity. |

| Rites of passage and initiation anthropology. | Arnold van Gennep; Victor Turner; academic summaries (The Rites of Passage). | Cultures historically use rites to transition people into adult roles; loss of rites reduces cultural transmission. |

| Critical responses / partisan cautions | Richard Hanania; commentary on “feminization” as a talking point (richardhanania.com). | Warns against reductive partisan uses of feminisation thesis; urges nuance and attention to incentives. |

VIII. DIVIDE ET IMPERARE—THE STRATEGY OF BABYLON

The Latin phrase Divide et imperare—“divide and rule”—was first attributed to Philip II of Macedon and later codified in Roman imperial strategy. It describes the deliberate fracturing of a people into smaller, competing factions in order to weaken collective resistance. Empires have always known this secret: unity is dangerous. Division is governance by confusion.

It is no accident that the Babylonian system, both ancient and modern, thrives on this principle. Babylon is not merely a city—it is a spiritual architecture, a counterfeit kingdom built upon confusion and fragmentation. The very name Babel (בָּבֶל, bāḇel) means “confusion” or “mixed speech” (Genesis 11:9). Its purpose was, and remains, to confuse language so that human cooperation collapses. When humanity cannot agree on meaning, it cannot agree on truth.

Today, that same spirit has re-emerged, not in the tower of bricks, but in the tower of identity politics. The new Babylon no longer builds monuments of stone—it builds ideologies. It sets man against woman, woman against man, the young against the old, the citizen against the neighbour, until all trust erodes and no unity remains.

“If a house is divided against itself, that house cannot stand.”

—Mark 3:25

This is not a random sociological accident—it is the oldest spiritual tactic known to the adversary. For Satan fears unity, for unity reflects the very nature of the Triune God. In the garden, the first fracture came when Eve and Adam were set against each other: “The woman You gave me…” (Genesis 3:12). The serpent needed only to whisper once to separate what God had joined. From that moment, the story of human history has been one of estrangement, not only from God but from one another as we play the blame-game.

In the modern age, this division has taken a subtler, more “civilised” form. The social engineers of our world—whether knowingly or unwittingly—perpetuate the strategy of Babylon. The goal is not liberation but disintegration: to dismantle the inner architecture of divine order. They dress rebellion in the language of rights, confusion in the language of compassion, and destruction in the language of progress.

WHO IS LARRY FINK?

Larry Fink is the Chairman and Chief Executive Officer of BlackRock, the world’s largest asset-management firm. He founded the company (originally part of Blackstone) and has steered it to manage trillions of dollars in assets (BlackRock is the Biggest Company You’ve Never Heard of).

Because BlackRock holds such a vast portfolio of investments, Fink is often described as one of the most influential individuals in global finance.

WHAT HE SAID: “YOU HAVE TO FORCE BEHAVIOURS”

In a 2017 (and subsequently recalled) interview, Fink said:

“You have to force behaviours, and at BlackRock we are forcing behaviours. And if you don’t force behaviours, whether it’s gender or race, or just any way you want to say the composition of your team, you’re going to be impacted” (BlackRock Responds to New Attacks).

In another interview he reaffirmed the approach that companies must act in ways that serve “a social purpose,” the question here is just what you define as your social purpose and how you propose achieving that purpose. Here actions speak louder than words. Serving social purpose

WHY THIS STATEMENT MATTERS

- Cultural Influence via Financial Leverage

Because BlackRock holds significant shares in thousands of companies worldwide, its voice in corporate governance is powerful. Fink’s statement shows that BlackRock intends to push companies to change internal culture (gender makeup, diversity, team composition) as a condition of investment or governance. This isn’t simply advising it is signalling enforcement.- Implications for Corporate Autonomy and Governance

When an asset manager of BlackRock’s scale declares it will “force behaviours”, it raises questions about how much companies still determine their own correctives vs. how much large investors determine them. It shifts power in the governance chain from company boards and management toward large institutional shareholders.- Market Share and Systemic Reach

BlackRock, along with peers like Vanguard Group and State Street Global Advisors, holds such a proportion of assets (and voting rights) that their collective influence spans most major public companies. One study notes they control voting blocs in nearly 90% of S&P 500 companies (Your Money, Their Vote). The dominance means when Fink speaks of “forcing behaviours,” he is not talking from a marginal investor’s position—he is speaking from structural power.- Cultural Change via Capital Markets

Fink’s remarks reflect a broader shift: capital markets are being used not only to allocate financial capital but to influence social and cultural norms inside corporations. This raises theological, ethical and ecclesial questions: when cultural mandates are enforced via investment capital, what happens to freedom of conscience, to subsidiarity, to local autonomy?SIGNIFICANCE FOR THE CHURCH, CULTURE & IDENTITY

From the perspective of faith communities, Fink’s words highlight how financial power can become a tool of cultural engineering—institutions being nudged or pressured to conform to certain values or behaviours, under threat of financial penalty or withdrawal of capital. This is not simply penalising people who run companies directly under his employ, it is also about companies who need access to finance under his control. For the Church, this is an invitation to reflection:

- We must ask: when the world’s systems leverage capital to shape identity, what does it mean for spiritual identity formed in Christ?

- If firms are being told they must change behaviours around gender and race under threat of investment impact, then the Church must reclaim its own formation practices of masculinity, femininity, covenant, and ownership before such external cultural forces define them.

- The sheer scale of BlackRock’s power means the Church cannot remain naïve about the intersection of money, identity and cultural formation. If we are going to reclaim healthy masculinity and femininity, we must see that part of the struggle is spiritual and economic, not merely moral.

The great question we must wrestle with in the modern discourse on equality is this: do we seek equality of opportunity, or equality of outcome?

WHAT IS EQUALITY?

It is not a trivial distinction. Equality of opportunity honours human dignity by allowing each person the freedom to rise, to labour, to create, and to contribute according to their unique design and ability. It affirms that all stand before the same open gate, though not all will choose to walk the same path or at the same pace. It recognises diversity within unity—the manifold gifts of humanity shaped under divine providence.

Equality of outcome, however, aims for uniformity rather than justice. It demands not that the race be fair, but that all runners cross the finish line together—regardless of effort, skill, or calling. This form of equality often begins with noble intentions but ends by suppressing excellence, punishing initiative, and eroding the very freedom that makes true flourishing possible. It replaces the moral vision of stewardship with the cold arithmetic of redistribution.

In Scripture, God’s justice never erases difference; it redeems it. The parable of the talents (Matthew 25) reminds us that the Master gives according to ability, expecting each servant to multiply what was entrusted. Heaven’s economy prizes faithfulness over sameness. To confuse equality with sameness is to deny the wisdom of divine variety—the differing glories of the sun, moon, and stars (1 Corinthians 15:41).

Thus, when we speak of equality in the Church or society, we must ask not merely how much everyone has, but whether everyone has been truly empowered to become what God created them to be. Equality of opportunity calls forth responsibility, gratitude, and creative excellence; equality of outcome, when absolutised, can breed resentment, dependency, and the death of merit.

The Kingdom ideal is not sameness but harmony—many members, one Body. It is not about levelling all heights, but about lifting the fallen so that each may stand in their rightful place before God.

True equality does not erase distinction—it honours it. It allows the feminine to be fully feminine and the masculine to be wholly masculine, without coercion, confusion, or competition. Authentic equality does not demand that each become what it is not; rather, it celebrates the sacred design within both.

When God created humanity, He did not make two copies of the same being. He made male and female—two reflections of one divine image, each bearing a unique expression of His nature (Genesis 1:27). To honour that difference is not to elevate one over the other, but to recognise the interdependence of both. The man is not complete without the woman, nor the woman without the man; together they reveal the fullness of the creative heart of God.

Modern culture often mistakes sameness for equality, insisting that liberation means dissolving all distinction. Yet this is not liberation—it is loss. When the feminine is told to imitate the masculine to prove her worth, and when the masculine is shamed into silence to appear gentle, both are robbed of their glory. Each becomes a shadow of itself, and the world grows poorer for it.

True equality calls us back to balance, not rivalry—to a harmony where strength and tenderness, reason and intuition, justice and mercy dance together without fear of hierarchy. In this divine order, the woman is not less because she nurtures, nor the man less because he protects. Both are stewards of different aspects of the same divine beauty.

In the end, equality as God intended is not about sameness of being, but unity of purpose. It is the restoration of right relationship—where difference becomes not a source of division, but a song of complementarity, echoing the Creator’s wisdom in every breath of man and woman alike.

In short: Larry Fink is not a marginal voice—he represents a node of immense financial power. His declaration that “you have to force behaviours” signals that some of corporate culture is now being shaped by capital requirements rather than exclusively by internal mission, board decisions or local morality. For those of us concerned with spiritual formation, gender identity, church culture and discipleship, this is a reminder that the broader cultural field is being shaped by forces far larger than most congregations realise. The Church must therefore both interpret and respond—forming believers whose identity and behaviour are rooted in Christ rather than capital-driven social mandates.

When men and women war against each other, the true enemy is forgotten. When churches turn against their own brothers and sisters, the spiritual battle is already lost. The devil no longer needs to persecute a divided Church; he merely needs to distract it.

A THEOLOGICAL COUNTERPOINT: UNITY AS SPIRITUAL WEAPON

True unity is not uniformity; it is harmony, and its only possible in Christ. Christ restores unity by reconciling opposites in Himself: heaven and earth, divine and human, masculine and feminine. On the Cross, He stretched His arms horizontally to reconcile humanity with humanity, even as He reached vertically toward the Father. The Cross is thus both axis and architecture—the meeting point of all relations.

It is no wonder that the early Fathers called Christ Pontifex Maximus, the “Great Bridge Builder.” For in Him, the river of the feminine and the banks of the masculine find their proper place once again. Apart, they flood and destroy; together, they form the landscape of life.

PHILOSOPHICAL ANALYSIS (Academic Reflection)

| Domain | Concept | Description | Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Political Theory | Divide et imperare | Strategy of control through division | Applied to gender, race, and class, creates perpetual conflict to weaken cultural coherence |

| Theological Anthropology | Ezer kenegdo (Genesis 2:18) | “Helper corresponding to him”; equal yet opposite | Reveals divine intent for complementary unity between masculine and feminine |

| Cultural Sociology | “Feminisation of the West” (Andrews, 2023) | Overcorrection of patriarchal imbalance producing instability | Results in institutional fragility and emotional governance |

| Spiritual Warfare | Babel → Babylon → Beast | Continuum of confusion to control | The final empire operates through ideological fragmentation |

| Ecclesiology | Koinonia (Communion) | Spirit-birthed unity that transcends fleshly identity | The Church must model what the world cannot manufacture: true oneness in Christ |

DEVOTIONAL REFLECTION

→ Beloved, if Satan cannot destroy the Church from without, he will divide it from within.

→ If he cannot silence a believer, he will confuse their sense of self.

→ If he cannot abolish the family, he will distort the roles within it.

But remember: unity is not the absence of difference—it is the consecration of difference unto a higher harmony. The same Spirit that hovered over the chaotic waters at creation now hovers over the chaos of our cultural moment, waiting for the word of faith to be spoken: “Let there be light.”

It is time for men and women to lay down their swords against each other and lift them instead against the true adversary. It is time to rebuild the walls of Jerusalem—not as fortresses of pride, but as boundaries of love that define and protect what is sacred.

IX. CONCLUSION: A CHURCH THAT INITIATES

Jephthah’s legal sentence—“whatever the LORD our God has given us, we will possess”—finishes not with a policy prescription but with a pastoral summons. The Church must learn again to give people what only the Church can give: initiation into a grown, sacramental, covenantal life in Christ. Men must be initiated into sacrificial, creative, ordered masculinity; women must be initiated into powerful, relational, and creative forms of femininity. Both parties must be forged by the cross so that neither becomes idolised or weaponised.

The present cultural moment is complex. Demographics matter. Laws and incentives matter. Family structure matters. Still, the deepest cure is spiritual: the slow and often painful work of formation that moves the believer from diffuse identity to stable, covenantal belonging.

Augustine’s line—“you were within me while I sought you without”—reminds us of the inward path: we are formed before we reform the world. But the inward path must bear outward fruit: stable families, robust institutions, and a public life shaped by people who have learned to die and to serve.

If you asked me bluntly whether the Church can reverse centuries of social change overnight, I would say no—the toothpaste-tube is not easily resealed. But the Christian task is not immediacy; it is faithfulness.

The Church can begin now to be a place of initiation: small churches that apprentice young men and women, liturgies that mean something, mentorship that gives fathering, and preaching that teaches covenant and spiritual communion. Out of such faithful work, new patterns emerge. Societies change slowly; the gospel works slowly—but surely—by forming persons who then form families, and who then influence institutions.

To accept your God-given role is not to bow in inferiority, but to rise in identity. There is no shame in strength, no weakness in tenderness, and no rivalry in divine order. As Stanislavski once said,

“There are no small parts, only small actors”

Likewise, in the great theatre of redemption, each role—male and female—is vital, sacred, and powerful when played with truth.

All is not lost yet!

“if my people [both godly men and women] who are called by my name humble themselves, and pray and seek my face and turn from their wicked ways, then I will hear from heaven and will forgive their sin and heal their land.” —2 Chronicles 7:14

Let us return, then, to Christ—our centre, our unity, our power. For only in Him do we recover what was lost: not competition, but covenant; not confusion, but calling; not division, but dominion. Together, in the Spirit of Christ, we rise again—not as adversaries, but as allies in the redemption of the world.

PRAYER

Father, You are the Giver of all good gifts. We confess our idolatry of the gods of approval, comfort and fleeting success. Help Your Church to be a place of initiation—a sanctuary where boys become men, girls become women, and all are taught to find their true place and power in Christ. Give us courage to name what is broken without bitterness, to repair what can be repaired by Your grace, and to steward what You have entrusted to us for the flourishing of our neighbours. In the name of Jesus, who through His cross unifies and matures, Amen.

QUESTIONS FOR FURTHER REFLECTION / SMALL GROUP STUDY

- Which gifts in your life feel like they came from God and which feel like they came from “the world”? How would recognising the giver change how you steward them?

- Where in your church or family do you see signs of spiritual infancy? How might a rite of initiation be responsibly introduced?

- How can men and women in your community begin to form apprenticeships that pass on adult virtues? Who could serve as mentors?

- What pastoral practices (retreats, fasts, public commitments) would move you from “believing with your mind” to “belonging with your life”?

- How can we hold critiques of cultural shifts (like feminization or Unwin’s thesis) without descending into scapegoating or moral panic?

Leave a comment