VIDEO

PODCAST

As we embark upon a study of the book of Daniel, it is essential to situate this narrative within the grand tapestry of human history, for it does not exist in isolation. The story of Daniel and Nebuchadnezzar unfolds against a backdrop of profound intellectual, spiritual, and cultural transformation across the known world. During this epoch, Confucius was shaping the ethical and social framework of Confucianism, while Laozi laid the foundations of Daoist thought in China. In India, Siddhartha Gautama—the Buddha—Mahavira, the reformer and spiritual luminary of Jainism, and the sages composing the Upanishads were revolutionising understandings of the human spirit, suffering, and the ultimate reality. Meanwhile, in the Mediterranean, Pythagoras and other thinkers were guiding the transition from the Greek Archaic Period into the Early Classical, giving rise to new modes of philosophical reasoning, mathematics, and cosmology.

This remarkable convergence of independent yet simultaneous developments, stretching roughly from the 8th to the 2nd century BCE, is what the philosopher Karl Jaspers would later term the Axial Age. Across continents and cultures, humanity was awakening to new ways of understanding existence, morality, and the divine. It is within this extraordinary and turbulent milieu that the book of Daniel emerges—an account of faith, memory, and divine sovereignty set against empires, human ambition, and the universal longing for order and meaning.

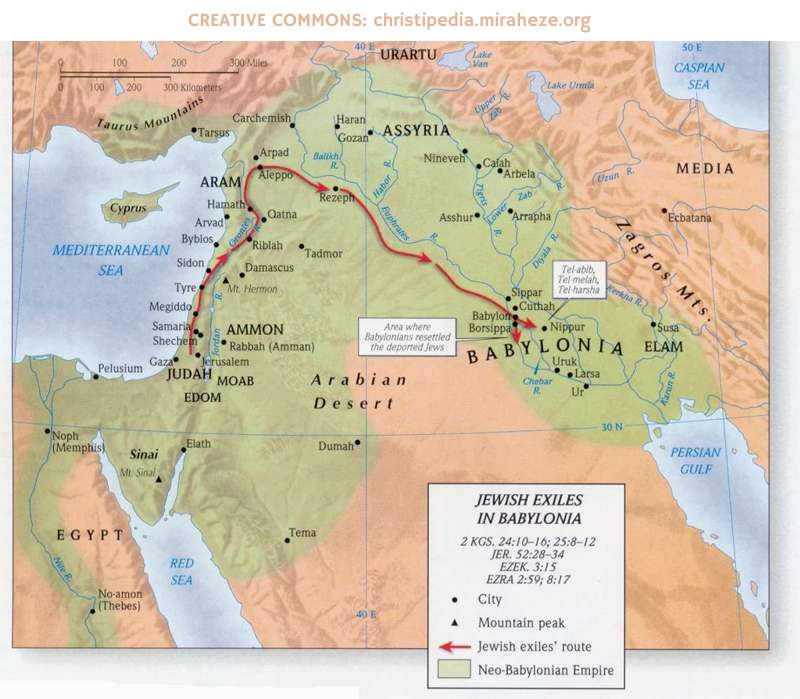

It is within this context that we encounter the narrative of the Babylonian exile, where the two tribes of Judah—whose name means praise—and Benjamin—whose name signifies son of my right hand—are carried into captivity. Their exile is not arbitrary; it is intimately connected to Israel’s covenantal fidelity. According to Scripture, the people had forgotten to keep the Sabbath, neglecting the sacred rhythm ordained by God. In response, a period of seventy years of exile is decreed to atone for the lost sacred time (Jeremiah 25:11–12, 2 Chronicles 36:21). These two names not only serve as monikers but also as identity and function in God’s economy.

The Sabbath stands apart among the Ten Commandments: it is the only commandment that is not “new” in the sense of being a civil or ritual law—it predates Israelite national identity, rooted in the creation narrative itself. Its commandment is inseparable from the word “remember” (zachor, זָכוֹר): “Remember the Sabbath day, to keep it holy” (Exodus 20:8). This commandment enjoins Israel to cultivate memory—spiritual attentiveness, sacred discipline, and fidelity to God’s order. In neglecting it, the Israelites experienced both a literal and metaphysical loss: the forfeiture of sacred time and, symbolically, a weakening of spiritual memory, the very faculty by which the heart “remembers” and aligns with God’s presence.

Thus, Daniel’s story is situated not merely in a historical exile but within a cosmic and spiritual framework. The exile reflects the consequences of forgetting God’s ordinance, and the prophetic narrative demonstrates that memory—guarding, keeping, shamar—is central to the preservation of identity, faith, and divine favour. In this light, the seventy years in Babylon are not solely punitive; they are restorative, designed to recalibrate Israel’s alignment with God’s covenant, to restore what was lost, and to cultivate the spiritual consciousness that Daniel and his companions would exemplify in the royal courts of Babylon.

In the tapestry of Scripture, names are never incidental. They are not mere labels; they are expressions of identity, conduits of authority, and often, mirrors reflecting the spiritual alignment of the one named. From the earliest chapters of Genesis to the prophetic visions of Daniel, the act of naming carries weight far beyond human bureaucracy—it is an imprint upon the soul, a declaration of allegiance, and a marker of memory. Naming is thus seen as an act of creating identity and consequent experience, s well as allegigence to and employing the help of a particular God in this case.

When we enter the study of Daniel, we encounter this truth immediately. The young men of Judah—Daniel, Hananiah, Mishael, and Azariah—are given new names by the king of Babylon: Belteshazzar, Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego. These names are not accidental; they are carefully selected to align these youths with Babylonian deities: Bel, the sun god, the fire deity, and Nebo, the god of wisdom. In this act, the exiles are invited—subtly, yet powerfully—to shift their spiritual allegiance. Names, in this instance, become instruments of cultural persuasion, tests of spiritual memory, and battlegrounds for identity.

“Will you not possess what Chemosh your god gives you to possess? And all that the LORD our God has dispossessed before us, we will possess.” –Judges 11:24

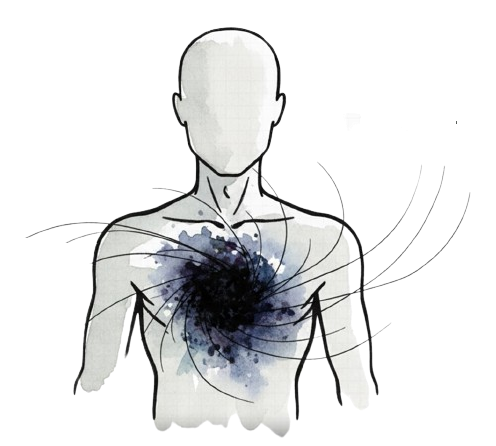

THE VACUUM OF GOD’S ABSENCE

Psalm 46:10 declares, “Be still, and know that I am God.” The Hebrew word for “be still,” raphah (רָפָה), conveys the necessity of ceasing human striving, surrendering control, and acknowledging divine sovereignty. When the presence of God is removed, as it was in Eden after the Fall, or after Christ’s ascension, humanity experiences a vacuum. In Latin, the principle is expressed as horror vacui: nature abhors a vacuum.

“In philosophy and early physics, horror vacui (Latin: horror of the vacuum) or plenism (fullness, plenty)—commonly stated as “nature abhors a vacuum“, for example by Spinoza—is a hypothesis attributed to Aristotle, later criticized by the atomism of Epicurus and Lucretius, that nature contains no vacuums because the denser surrounding material continuum would immediately fill the rarity of an incipient void.

Aristotle also argued against the void in a more abstract sense: since a void is merely nothingness, following his teacher Plato, nothingness cannot rightly be said to exist. Furthermore, insofar as a void would be featureless, it could neither be encountered by the senses nor could its supposition lend additional explanatory power.” –Wikipedia

What we call nothing or the infinite, is the space where God exists.

The human heart, left unchecked, abhors it even more, because it mistakes the “void” in space and time as nothing physically, yet it is the doorway to everything spiritually. Thus the sacred duty of mankind is to keep this doorway open. This is the definition of priesthood.

- Blaise Pascal (1623–1662): In his Pensées, Pascal similarly observes the innate human yearning for the divine:

“There is a God-shaped vacuum in the heart of every man which cannot be filled by any created thing, but only by God, the Creator, made known through Jesus Christ.”

Pascal’s insight parallels Augustine: the longing for the transcendent is universal, and misdirected human desires often manifest as pursuit of cultural gods, secular success, or physical pleasures.

- C.S. Lewis (1898–1963): In Mere Christianity, Lewis reflects on the innate dissatisfaction humans experience:

“If I find in myself a desire which no experience in this world can satisfy, the most probable explanation is that I was made for another world.”

This resonates with the exilic experience in Daniel: the exile’s longing for home, identity, and spiritual truth is a manifestation of the God-shaped void within. The Babylonian system could not satisfy that longing; only adherence to Yahweh could. Thus, the Babylonian exile becomes a metaphor for the spiritual exile from God’s presence. Judah had forgotten God spiritually in practice and experience and thus the physical world mirrored their divine alienation.

This absence is not merely spatial; it is spiritual and temporal. Left to its own devices, the human imagination seeks to fill it, often with rituals, hierarchical structures, or ideological, political or economic systems that masquerade as divine authority. The exiles in Babylon, observing the grandeur of the empire, its wealth, and its complex religious systems, were confronted with such a vacuum. They could no longer rely on the visible presence of God symbolised by the Temple, and the temptation was to substitute human order and Babylonian deities for divine guidance.

By neglecting the Sabbath, the people were, in effect, declaring that human activity—commerce, busyness, and self-directed labour—was more valuable than sacred rest. The refusal to cease from work symbolised a devotion not to God, but to the “god of business,” Mammon, elevating productivity, wealth, and worldly success above divine order. In this sense, the Sabbath is not merely a day of rest; it is a counter-cultural act of allegiance, a declaration that God alone is the source of provision and authority.

The word Sabbath comes from the Hebrew shabbat (שַׁבָּת), derived from the root shavat (שָׁבַת), meaning “to cease, to rest, to desist.” Etymologically, it carries both the sense of cessation and the directive to remember (zachor, זָכוֹר) the sacred rhythm ordained by God. This connection underscores the dual purpose of the Sabbath: it is both a practical cessation of ordinary work and a spiritual exercise in remembrance—an intentional posture of attention to God. By forgetting the Sabbath, Israel had forgotten to “remember” God, and thus the sacred rhythm of life and time was disrupted.

It is vital to note that Sabbath observance for Christians is not a legalistic injunction against activity on a particular day of the week. Paul affirms this in Colosians 2:16-17,

“Therefore let no one pass judgment on you in questions of food and drink, or with regard to a festival or a new moon or a Sabbath. These are a shadow of the things to come, but the substance belongs to [is found in] Christ.”

The Sabbath is not merely about refraining from work; it is a spiritual posture—a voluntary surrender of self-sufficiency and activity (practice) in order to access God’s strength.

By ceasing our endless “striving” for safety, one participates in a cosmic mechanism: aligning human rhythm with the divine rhythm of “rest,” acknowledging God as sustainer, and allowing His power to flow through voluntary weakness.

2 Corinthians 1:9,10

In essence, Sabbath-keeping is an act of spiritual memory (shamar), a deliberate exercise in trust and devotion, declaring that God, not Mammon, is the ultimate provider and judge. It is both restorative and formative: restorative because it replenishes the soul, and formative because it cultivates a consciousness attuned to God’s presence, even amidst the demands of worldly life.

| Term | Hebrew / Greek | Meaning | Spiritual Insight |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sabbath | שַׁבָּת (shabbat) | To cease, to rest | Voluntary cessation to access God’s strength |

| Root of Sabbath | שָׁבַת (shavat) | To desist, pause | Spiritual posture of surrender and remembrance |

| Remember | זָכוֹר (zachor) | To recall, guard, keep | Guarding sacred memory and divine alignment |

| Mammon | μαμωνᾶς (mamōnas) | Wealth, worldly devotion | Counterfeit saviour replacing God |

This framing ties directly into Daniel’s story: the exile of Judah and Benjamin, the prophetic warnings, and the preservation of spiritual memory in the midst of Babylonian pressure all point to the profound necessity of remembering God and ceasing from self-directed busyness.

The Sabbath, far from being a restriction, is an invitation to spiritual empowerment, a cosmic rhythm through which the soul participates in divine order.

Psalm 127:1–2 reinforces this principle:

“Unless the LORD builds the house, its builders labor in vain; unless the LORD protects the city, its watchmen stand guard in vain. In vain you rise early and stay up late, toiling for bread to eat— for He gives sleep to His beloved.”

True—that is, lasting—success, sustenance, and blessing derive from God alone. The human tendency to seek these from alternative sources—education, economics, politics, wealth accumulation—illustrates how we consistently attempt to fill the vacuum left when we ignore or forget God.

However, when we cease from our ceaseless striving for success—what the Hebrews sometimes term halel, the pursuit of fortune, success, praise, or luck—and instead set aside a designated time for spiritual watchfulness, a profound transformation occurs.

This act of voluntary cessation is not passivity but a deliberate posture of shamar, to stand guard, to keep attentive. In that sacred pause, God Himself assumes the watch over our lives, accomplishing for us what we could never accomplish on our own.

The principle is cosmic and deeply practical: human effort, unanchored in divine alignment, produces anxiety, competition, and societal disorder which all inevitably lead to collapse. All the fractures of human society—from injustice to corruption, from strife to neglect—flow ultimately from forgetting God, from neglecting Him in spiritual practice, from failing to honour the rhythms He has ordained. When we ignore this divine cadence, we attempt to substitute human ingenuity, political systems, or wealth accumulation for the sustaining presence of God. Colossians 1:17 states,

“He is before all things, and in him all things hold together.”

That is to say, outside of Him they fall apart.

When we intentionally “cease,” even briefly, we participate in a rhythm far greater than our own: a rhythm in which divine power intersects with human limitation. By standing watch spiritually, we allow God to act on our behalf. This is the true Sabbath principle—not a prohibition of activity, but a declaration that our strength, wisdom, and provision are rooted in Him, not in human effort or worldly success. The act of remembering, guarding, and ceasing, therefore, becomes both a spiritual discipline and a conduit of divine intervention, restoring order where human striving alone can only produce disorder, exhaustion and collapse.

NAMES, IDENTITY, AND CULTURAL GODS

The new names given to Daniel and his companions are not merely cultural assimilation; they reflect a fundamental principle: the perceived source of success dictates allegiance. In Babylon, gods were seen as dispensers of wisdom, strength, and influence. By renaming the youths, Babylon was signalling that their prosperity and survival depended on these foreign powers.

Yet the Hebrew names carried enduring spiritual significance:

Through this, Scripture demonstrates a central tension: the physical and temporal forces of Babylon seek to replace divine authority, yet spiritual fidelity remains anchored in God’s names and identity, and not in man-made names and identity.

- Daniel – “God is my judge” (Dan = judge, El = God).

- Hananiah – “Yahweh is gracious” (Hanan = gracious, Yah = God).

- Mishael – “Who is like God?” (Mi = who, Shael = like, El = God).

- Azariah – “Yahweh has helped” (Azar = help, Yah = God).

HEBREW ETYMOLOGY AND SPIRITUAL MEMORY

The concept of memory, or spiritual remembrance, is crucial in Daniel. The Hebrew word shamar (שָׁמַר) encompasses guarding, keeping, and remembering. Forgetfulness, in the biblical sense, is not mere cognitive failure but spiritual amnesia—a susceptibility to external persuasion and idolatry.

ETYMOLOGY

- Hebrew שָׁמַר (shamar, to guard/watch/preserve) → שׁוֹמֵר (shomer, watchman) → שְׁמִירָה (shemirah, guarding)

- Linked across languages: German Schirm/Schrim (shield/screen), English scrim, rugby scrum, Japanese samurai and Mamoru (guard/protect), English smart (mindful/clever)

- Conceptual metaphor: “Memory = guarding” — what is kept in mind is guarded.

- Related concepts: hearing/obeying, remembering, screening, shielding, thorn protection.

In contrast, apeitheō, a Greek term discussed in prior studies, conveys a refusal to be persuaded. Spiritual practice (sabbath) is the art of choosing the spiritual narrative over being seduced by the physical senses.

Daniel and his companions exemplify resistance to such persuasion: their physical senses are confronted by foreign food, clothing, and culture, yet their spiritual consciousness (shamar) remains vigilant.

This battle between physical and spiritual consciousness is universal, transcending time and culture.

| Hebrew Term | Meaning | Context in Daniel | Spiritual Insight |

|---|---|---|---|

| שָׁמַר (shamar) | To guard, keep, remember | Maintaining covenantal identity | Spiritual memory preserves fidelity to God |

| דָּנִיאֵל (Daniel) | God is my judge | Individual identity | Reliance on God’s judgment over human authority |

| חֲנַנְיָה (Hananiah) | Yah is gracious | Prophetic witness | Trust in divine grace, not foreign power |

| מִישָׁאֵל (Mishael) | Who is like God? | Inquiry of faith | Affirmation of divine supremacy |

| עֲזַרְיָה (Azariah) | Yah has helped | Divine intervention | Recognition of God’s sustaining help |

BABYLONIAN GODS AND THE PURSUIT OF SUCCESS

Babylonian religion served as a framework for understanding prosperity. Success was not merely practical but metaphysical: gods conferred wisdom, military strength, political influence, and even health. The human tendency, both then and now, is to imitate the successful without discerning the divine order that undergirds true blessing.

Acts 17:26–27 affirms:

“And hath made of one blood all nations of men… that they should seek the Lord, if haply they might feel after him, and find him, though he be not far from every one of us.”

God determines the times and boundaries of human habitation, yet humanity frequently substitutes temporal systems, cultural idols, or institutional rituals in place of seeking Him—often as a conscious or unconscious attempt to replace His authority. When we neglect to steward the portion entrusted to us in alignment with God’s principles, that stewardship inevitably reverts to its rightful Owner—God. This pattern resonates through history, providing insight into the cycles of Western colonial expansion, exploitation, and particularly relevant to us, the cultural, moral decline and impeding collapse of Western civilisation.

| Babylonian Deity | Function | Daniel Name Equivalent | Israelite Faith Contrast |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bel | Chief god, kingly authority | Belteshazzar | God as ultimate sovereign |

| Sun deity | Solar success, power | Shadrach | God as light and sustainer |

| Fire god | Purification, strength | Meshach | Holy Spirit and divine refining |

| Nebo | Wisdom, writing | Abednego | God grants true understanding |

The exiles’ success and survival depended not on these deities, but on remaining faithful to Yahweh—a principle that resonates across history for all who seek enduring blessing.

NUMERICAL AND SYMBOLIC FRAMEWORKS

Babylon’s obsession with time and structure is reflected in its base-60 numerical system—the origin of our time keeping. Timekeeping, astronomy, and administrative control were linked to divine authority, reinforcing the idea that human order could emulate, or even replace, divine governance.

In contrast, Israel’s covenantal symbolism revolves around judgement (base 10, Israel) and extension into covenantal relationship (Base 2, Judah). Daniel, positioned in Babylon’s temporal and political systems, becomes a living testament to God’s sovereignty amidst human order as he actively aligns himself with Jahweh.

| System | Numerical Base | Symbolism | Spiritual Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Babylon | 60 | Time, order, human authority | Reliance on temporal structures as surrogate gods |

| Israel | 10 | Judgement, justice | Divine order flows from the throne of God. |

| Judah | 2 | Covenant partnership | Spiritual fidelity, partnership, exponential power |

AXIAL AGE CONTEXT (800–200 BCE)

Daniel’s era coincides with a remarkable global convergence of thought and spiritual inquiry. This period, termed the Axial Age by Karl Jaspers, saw independent, simultaneous developments of philosophy, religious systems, and metaphysical reflection during the Age of Aries (organisation and codification):

| Region | Key Figures / Movements | Approx. Dates | Relevance to Daniel |

|---|---|---|---|

| China | Confucius, Laozi | 551–479 BCE | Ethics, governance, harmony |

| India | Buddha, Mahavira, Upanishads | 600–400 BCE | Inner consciousness, detachment |

| Greece | Pythagoras, early philosophers | 580–500 BCE | Logic, order, cosmology |

| Persia | Zoroaster | 1000–600 BCE | Dualism, cosmic struggle |

| Israel/Babylon | Prophetic monotheism | 600–500 BCE | Faithfulness amid exile |

This demonstrates a universal human search for order, meaning, and success and human growth phases as determined by divine timing. In Daniel, we see a microcosm of this Axial Age tension: the pursuit of wisdom and prosperity, yet anchored in divine fidelity.

GEOPOLITICAL AND CULTURAL INSIGHTS

Babylon’s political strategy included transporting skilled exiles to consolidate power and integrate knowledge. These exiles were educated in literature, administration, and science, effectively merging Israelite intellect with Babylonian power structures.

TRADE ROUTES OF BABYLON (AND BY EXTENSION, JUDAH)

Babylon sat at the centre of the ancient world’s most important trade corridors. Their network connected:

1. Mesopotamia → India

- Through the Persian Gulf.

- Trade in spices, beads, ivory, textiles.

2. Mesopotamia → Arabia → Africa

- Via caravan routes.

- Goods included frankincense, myrrh, gold, exotic woods.

3. Mesopotamia → Anatolia (Turkey) → Aegean

- Metals (tin, copper), textiles, wine, olive oil.

4. Mesopotamia → Levant → Mediterranean

- Judah existed on the crucial land bridge between Egypt and Mesopotamia.

- Spices, oils, cedar, wine, wool.

5. Mesopotamia → Central Asia → China

Via early proto-Silk Road routes:

- Jade from Xinjiang.

- Lapiz lazuli from Afghanistan.

- Early silk appearing in small quantities.

So in short:

Babylon sat at the crossroads between Mediterranean, Africa, Persia, Central Asia, and early Chinese trade networks.

Daniel’s context reflects both the challenges and opportunities of a globally connected intellectual environment, emphasizing the tension between human order and divine sovereignty.

WHAT HAPPENED IN BABYLON LEADING UP TO THE FALL OF THE JEWISH CAPITAL

BACKGROUND

The fall of Jerusalem in 586 BC—when Nebuchadnezzar II destroyed the First Temple and exiled the Jews to Babylon—did not happen in a vacuum. It was the result of a century of geopolitical shifts, rapidly rising empires, failing vassal states, and the collapse of older powers like Assyria.

Below is the sequence.

1. ASSYRIA COLLAPSES (c. 650–612 BC)

- For centuries, Assyria dominated the Near East.

- But internal instability, rebellions, and external pressure weakened it.

- Babylon, under Nabopolassar, allied with the Medes and Scythians.

- In 612 BC, they destroyed Nineveh, ending Assyrian supremacy.

Why this matters:

Judah had depended on shifting alliances between Egypt and Assyria. When Assyria fell, Judah was left exposed.

2. RISE OF THE NEO-BABYLONIAN EMPIRE (612–539 BC)

This is the empire of Nebuchadnezzar II, one of the most powerful and sophisticated kings in the ancient world.

KEY DEVELOPMENTS

- Babylon becomes the new centre of trade, science, astronomy, and architecture.

- Nebuchadnezzar builds:

- The Ishtar Gate

- The Processional Way

- The famed hanging gardens (disputed historically)

JUDAH BECOMES A VASSAL

- Babylon defeats Egypt at Carchemish (605 BC).

- Judah becomes a Babylonian vassal after King Jehoiakim submits.

- Babylon expects loyalty and tribute.

3. THREE WAVES OF DEPORTATION

FIRST DEPORTATION (605 BC)

- After Carchemish, Nebuchadnezzar’s first deportation includes Daniel and nobility.

SECOND DEPORTATION (597 BC)

- Jehoiakim rebels; Babylon crushes Judah.

- King Jehoiachin, Ezekiel, and 10,000 others taken.

FINAL DEPORTATION (588–586 BC)

- Zedekiah rebels under false hope of Egyptian support.

- Babylon besieges Jerusalem for ~18 months.

- City falls in 586 BC.

- Temple destroyed.

- Third deportation.

PRESENCE OF GOD IN DANIEL

The triumph of Daniel and his companions lies not in political power, but in spiritual fidelity. Through fasting, prayer, and unwavering devotion, they maintain shamar, preserving covenantal memory and identity. Their prophetic insight, ability to interpret dreams, and integrity in governance flwoing from their “remembering Jehovah” underscore a fundamental principle: God alone sustains, provides, and grants wisdom. It is only when we “forget” (spiritual consciousness) God that we get into trouble (cf. Deut 8:1-11).

| Name | Hebrew Meaning | Babylonian Name | Divine Source of Success |

|---|---|---|---|

| Daniel | God is my judge | Belteshazzar | God judges and sustains |

| Hananiah | Yahweh is gracious | Shadrach | God’s grace overflows |

| Mishael | Who is like God? | Meshach | God’s uniqueness triumphs |

| Azariah | Yah has helped | Abednego | God’s help is sufficient |

MODERN LESSONS

- Guard spiritual memory (learning) and remembrance (spiritual practice) in a culture of distraction and idolisation.

- Identify modern “Babylons”—corporations, political ideologies, social movements—that promise success while displacing God i.e. pseudo or false saviours

- Resist persuasion by physical senses (peitho) in favour of spiritual consciousness.

- Steward God’s gifts faithfully, rather than seeking substitutes.

DEVOTIONAL REFLECTION

Meditation: God alone sustains our lives and work. Where we perceive emptiness or lack, it is often an invitation to trust Him. Like Daniel, we are called to maintain memory of His presence amidst worldly pressures.

Prayer: Lord, preserve my memory of You. Let me discern truth from illusion, grace from imitation. Help me resist the idols of this age and rely solely on Your sustaining presence.

Reflection Questions:

- In what areas of my life am I substituting God with “artificial gods”?

- How can I guard my spiritual memory (shamar) daily?

- Where do I allow physical persuasion (peitho) to override spiritual consciousness?

- What lessons can I draw from Daniel’s integrity in exile for my personal and professional life?

- How does understanding the Axial Age context deepen my appreciation for God’s universal sovereignty?

CONCLUSION

The study of Daniel invites us into the tension between divine presence and human substitutes, between memory and forgetfulness, and between temporal persuasion and eternal truth. Daniel stands as a paradigm of spiritual consciousness, faithfulness, and wisdom. By guarding memory, resisting idols, and embracing God’s sustaining presence, we restore the vacuum left by His absence—not with rituals, names, or human structures, but with the living, abiding God of Israel.

1. DANIEL WAS FROM THE KINGDOM OF JUDAH

When the Book of Daniel opens (Daniel 1:1–6), he is described as part of:

- “the children of Judah”

- Noble, royal-class youths taken from Jerusalem, the capital of Judah.

The Northern Kingdom (Israel) had already fallen over 120 years earlier (722 BC) to Assyria.

Daniel lived long after that.

So Daniel is a Judean exile — not an Israelite from the northern kingdom.

2. BABYLON CONQUERED JUDAH, NOT ISRAEL

ISRAEL (NORTHERN KINGDOM)

- Fell in 722 BC to Assyria

- Daniel was not alive

- No part of Daniel takes place there

JUDAH (SOUTHERN KINGDOM)

- Includes the tribe of Benjamin

- Fell in three deportations (605, 597, 586 BC) to Babylon

- Daniel was taken in the first deportation (605 BC)

- EVERYTHING in the Book of Daniel is connected to Judah’s exile

This is why Daniel is in Babylon — because Judah fell, not Israel.

3. DANIEL REPRESENTS THE ROYAL HOUSE OF DAVID

He is explicitly said to be from:

- The tribe of Judah

- Possibly connected to Davidic or aristocratic lineage

Babylon specifically targeted:

- Royal sons

- Noble youths

- Skilled students

- Priestly families

Daniel was chosen from this class.

4. SUMMARY: THE KINGDOM THAT DANIEL DEALS WITH IS JUDAH

| Book | Kingdom Involved | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Daniel | Judah | Daniel is a Judean exile in Babylon/Persia |

| Israel | Already destroyed | Not part of Daniel’s story |

5. WHY THIS MATTERS THEOLOGICALLY

- The Messianic lineage is from Judah, not Israel — Daniel stands in that stream.

- The Temple, priesthood, and covenant worship were all in Jerusalem (Judah).

- Babylon’s attack on Judah was spiritually catastrophic — Daniel becomes a symbol of remaining faithful when the kingdom collapses.

Daniel is, in effect: The representative of Judah in a foreign empire, carrying the light of God into Babylon and then Persia.

Through the life of Daniel, we discover that true spiritual fidelity stands above every political order, outlasts every empire, and remains untouched by the swirl of cultural influence. In our own age—marked by global upheaval, technological acceleration, and tectonic shifts in political and financial power—his witness calls us back to vigilance, holy memory, and unwavering faith. Daniel shows us how to remain steady when the architecture of society is being rewritten around us. Through intentional spiritual practice, we anchor our souls to the unshakeable Rock of Christ, refusing to be swept away by the shifting sands of circumstance. His story becomes our roadmap for living faithfully in a world being reshaped before our eyes.

PRAYER

Father,

You are the God who sets the boundaries of nations and the seasons of our lives. You see the rise and fall of kingdoms, and yet You also see the quiet trembling of an honest heart seeking You in the dark. Carry me just as You carried Daniel .Teach me to remain faithful when I am far from the familiar.

Teach me to trust Your timing when circumstances look like collapse.

Teach me to stand, to pray, to discern, and to shine as Daniel did.Let my identity be anchored in You—not in the environment, not in the pressure of culture, not in the voices of those who bowed to other gods.

Place in me the same excellent spirit that distinguished Daniel, and the same unwavering loyalty that refused compromise.May every Babylon You allow become a place of revelation.

May every trial become a place of wisdom.

May every shifting season draw me closer to You.And when You open the windows of destiny, as You did for Your people through Cyrus, give me eyes to recognise deliverance, courage to walk through it, and gratitude to steward it well.

I trust Your sovereignty.

I trust Your timing.

I trust Your purposes for my life.In Jesus’ Name, Amen.

FIVE QUESTIONS FOR REFLECTION

- Where in my life do I feel as though I am in a personal “exile,” and how might God be shaping me there the way He shaped Daniel?

- What compromises am I tempted toward when I feel pressure from the “Babylon” around me, and how can I respond with integrity?

- How does understanding that God sets the boundaries and seasons of nations (Acts 17:26) change the way I interpret my current circumstances?

- In what ways might God be preparing me—like Daniel—to carry influence in places I never expected or desired?

- What small daily practices (prayer, Scripture, obedience) can help cultivate the “excellent spirit” Daniel carried, even in a hostile culture?

Leave a reply to DEVOTIONAL: FAITHFUL IN A SHIFTING WORLD – The Hungry Hearts Collective Cancel reply